Archivists do more than paperwork: they handle people’s entire lives. Also, the defeat of an archivist, and what all this has to do with the Stone Guest.

How did I come to participate in Memorial? My friend and colleague Alyona told me, "We have an opening. There’s a vacancy in recruitment. Now we have this request: a person wants someone to come to see her and gather up her archive. Keep in mind that this is the first and last time you will see her in your life. You'll come, you'll pick it up, and you'll leave.” That person turned out to be my closest friend for the rest of my life. I went to her funeral.

As it happened, indeed, I came, she gave me a huge archive. She went to put the kettle on, and she had a book open on her bedside table. Well, it's always interesting to see what a person reads. And it's not like I'm being rude. I go up and look—the book is open, and there is a group photo, and my father is in it. The book was dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the institute where my father worked and where the husband of this informant of ours worked.

So it was a sign to me that it probably makes sense to work a little bit at Memorial. And I later became convinced of this many times over the years.

I'm an archivist by accident. I happened to come there, and I realized that this is a world of magic and fairy tales. And that it's just like King Koshchei drooling over gold. Because suddenly some unknown things are revealed.

An ordinary archivist—he sits at a table and there is a mountain of papers in front of him. He numbers them, puts them in a box, labels them, and when five o'clock strikes, he goes home. The Memorial archive is somewhat different. I don't know why—it probably happened historically. Or maybe we think that we’re not just doing paperwork, but we have people’s fates in our hands.

I guess I just accidentally said something important. Because it's probably true. And when a set of documents ends up in our hands, we understand that there is a person behind them. Then you can do whatever you want: you can put it in an envelope and forget it, or you can try to understand what part of it can be continued. What kind of continuation can there be if we are talking about the past? But nevertheless.

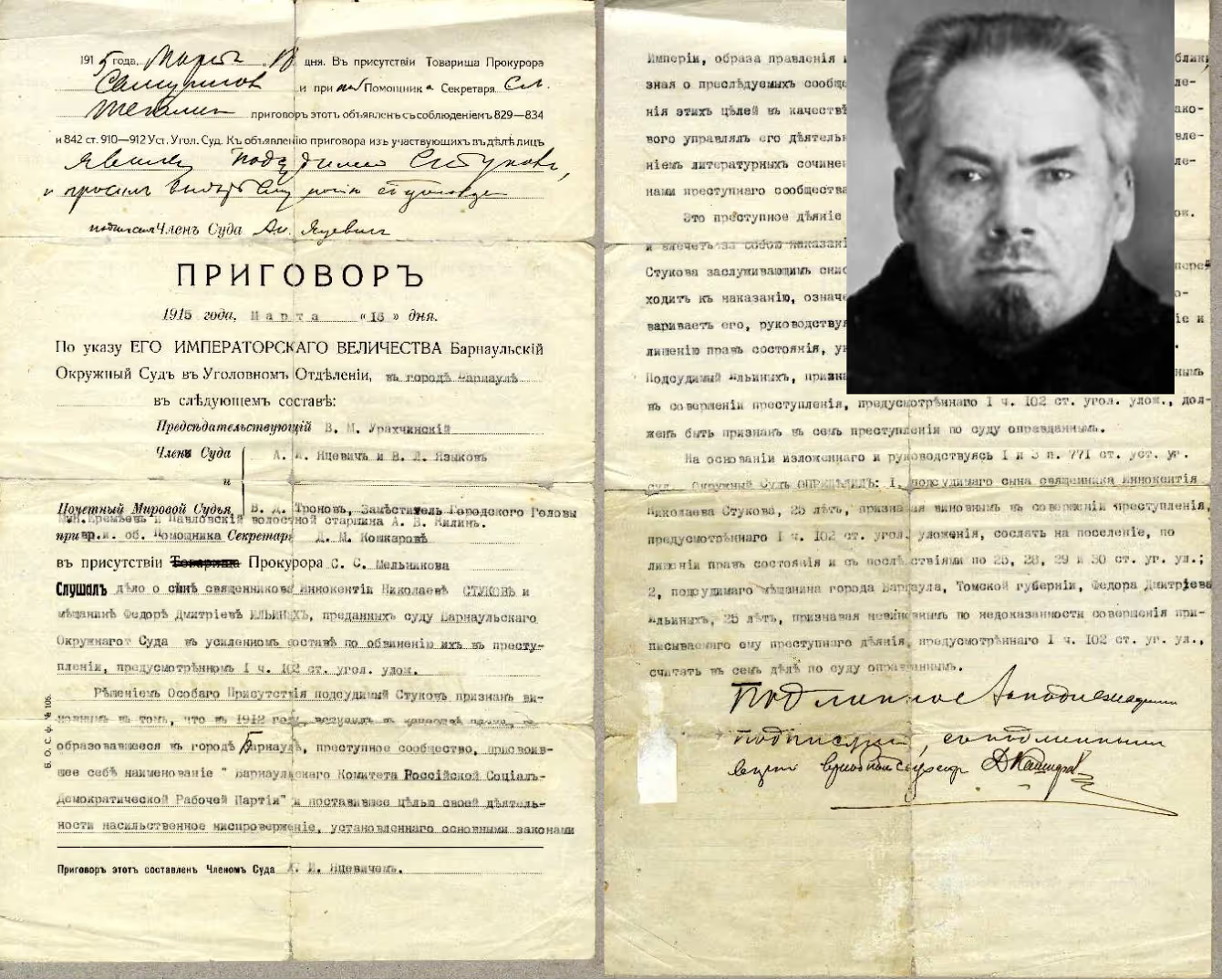

At some point, quite by chance, we got this one archive in which there was an array of documents, and it was isolated into a separate topic. It turned out that these were pre-revolutionary letters from a man in prison. He was serving time doing hard labor under the tsarist regime. And these are his letters from [old-fashioned word for prison] (if we have a pre-revolutionary archive, then we use the appropriate vocabulary). He writes these letters to his wife. His prison conditions are quite harsh: he’s in solitary confinement. As far as I remember, he has a small window. Through this small window, he sees some changes in nature: snow piles up, or maybe a flower blooms. He even writes poetry about it and sends it to his wife.

The surname is not the most common, so I wondered what happened to him next. By a simple search, I saw that this man was a serious revolutionary. His whole desire was the happiness of the people and victory over the accursed tsarist regime. And now, [he thought], there will be a happy society, and we’ll build it with our own hands. Well, he was shot in '37, of course.

The revolution freed him from that very prison sentence. He was a Leninist. And he had a good career, but in '37 he was shot. I found out that he had been shot. It was easy: we have a database, and I checked it without getting up from my chair. And then I tried to see if there was anyone with the same patronymic and last name.

Honestly, no one asked me to do this. It was solely a desire to continue the search so that we understand what's next. Otherwise, we get it, the last letter was written sometime in 1916, then we know that he was shot in 1937, and that's it. But that leaves a lot out, doesn’t it?

Well, anyway, we found his son, who is no longer alive, and we found his granddaughter. And I wrote to his granddaughter. We have Facebook, and a lot of people are on Facebook. You write a private message. After a while, she responded. And I told her that we have letters from your grandfather, would you like to read them? And she came to see us.

I even remember that she lived outside the city and worked somewhere. And she asked: "Is it possible on the weekend? Because I can't make it on work days." But for the sake of such an occasion, of course, it is possible. And it was just the two of us. There was no one else.

And she was in shock as she read those letters. And she told something amazing, that she now saw him in an unexpected light, because for her father he was, as always happens, a perfect knight of the revolution who died on the barricades. He was shot, then he was rehabilitated. That's why he's such a hero. Like the Stone Guest [a reference to Pushkin’s version of Don Giovanni]. She said, "Listen, he's writing poetry, he's alive. But he's crying here." But the Stone Guest never cries.

So we gave her a living person in this way. Is this the work of an archive or not? Does anyone need this, except for this one woman and us, the employees of Memorial, who pulled on this thread and connected people who are strangers to each other but who have the same name? Is it happiness for them? Relief? Or did we put a burden on her shoulders? What did we do?

I want to give another example now, and it is also quite extreme. I’ll tell you openly that, for me, this was a defeat. Also by accident, as it always happens: these accidents happen every day; nevertheless, they are still accidents. In a completely different archive, there was this bit inserted. It’s very interesting. That is not our period at all, because we consider that our period is from 1917 to 1991. But this is from the First World War.

A woman, a nurse from the First World War, writes these letters to her cousin. Then she continues to write letters to her cousin. And so he writes and goes on writing up to the 1960s. And we learn from this large correspondence that at first she was a nurse, a nurse in the First World War. That her father also fought in the First World War.

And I understood…I figured out that this is the amazing General Tumanov, a prince from Georgia. The photographs are of indescribable beauty. Here are these pre-revolutionary photographs on cardboard boxes, where it is written on the back that all the negatives are preserved. It's all just a delight for collectors and archivists, who are also collectors. But this isn’t our period. It’s the First World War. And the man was not injured. And with some effort of will, I managed to find his grandson. I find it funny, because there was a notebook with phone numbers from the 1970s attached. I called that number, and it was the right number.

I told him, "You know, we have pictures of your grandmother." And I know from the letters that our heroine, Tamara Tumanova, has a son who divorced his wife, and she has a son and a grandson. And she is very lonely and lives in Tbilisi, where she heads the piano department at the Tbilisi Conservatory. She has no one, because her son is in Moscow, her grandson is in Moscow, and the children are divorced. She doesn’t ever see her son, and she’s miserable. She is very worried that she has such a lonely old age, that she is deprived of communication with her only and beloved grandson.

I call him and tell him, "You know, we have photos of your grandmother. You can come and see them." He says, "I'm not interested in that." I waited a bit. I came up with a beautiful story for myself: well, I called a man on the phone, probably not too young anymore, and dumped this mass of information on him. Everyone’s afraid of scammers now. Everyone’s afraid of crooks. He probably thinks I want something from him. Maybe I explained it awkwardly. Maybe he thought that I wanted to come to visit him, and he was scared, and he didn't want to let anyone in.

I call him a month or two later and say, "We talked a while ago. We have photos of your grandmother. We’ve scanned them. If you give me your email address, I'll send them to you." He says, "I'm not interested in that." I had just this one case like this, but somehow I took it really hard. I imagined that if someone called me and said, "I have photos of your grandmother," God, I would run barefoot to see him.

Quite a long time ago, one of our co-workers was in Kolyma, and when she was leaving, she went straight to the ship…what do we call them now? Ships? Steamships? Well, something that was leaving Kolyma. Someone told her, "You know, we found this," and gave her a bundle of letters. A pack of camp letters. She had gone to Kolyma on an expedition. Our staff went to Kolyma many times in the 90s on expeditions to investigate abandoned camps, do archival work, and all sorts of things. She was given this bundle of letters. We examined them, studied them, and it turned out that they were from a very famous Trotskyist. His last name is Bodrov. He was repeatedly arrested and repressed. He went to prison many times. He was an ideological Trotskyist: even when Trotsky was exiled to Kazakhstan, he went there and grew a beard so that he looked like a coachman, a cabman. So there was this connection to Trotsky.

These were several postcards addressed to his children. He wrote them while imprisoned in Kolyma. And what happened after that? The man writes a letter and puts it in a mailbox. Then the censors are activated, because this is camp mail. Some mailpieces they send on to the addressee, and some get added to his file. It was something that had been filed in the camp file. And then at that moment, in the 90s, departmental archives were being cleaned out in Kolyma. And whatever they thought was unnecessary, they just threw away. Someone picked it up, and our Irina was there, and they gave it to her. And it’s been preserved.

So, one day, we’re doing our work. The phone rings, and in this case it's not me who picks up the phone, but my colleague. She holds a conversation, sounding disturbed, then hangs up the phone. She says, "Listen, Bodrov's granddaughter called from Paris." I say, "What do you mean, Bodrov's granddaughter?" "I mean Bodrov's granddaughter." I said, “And?” She said, "I told her that we have letters from her grandfather. She said, 'I’m flying to see you.'" And she really did.

The most interesting thing is that no one in the family knew that he was a Trotskyist. In the family, his wife passed on information that he was a real communist, a Bolshevik: there were no conflicts with the Party line. Well, he died. He died like everyone else. So it literally fell from the sky. It's all a miracle.

Начать ваш собственный архивный поиск можно с электронных версий архивов:

Архив Научно-информационного центра «Мемориал»

Архив Исследовательского центра Восточной Европы при Бременском университете

You can start your own archival research with the digital archives:

Memorial Society archive

Feniks Database of the Archive of the FSO Bremen

_______

Sie können Ihre eigene Archivrecherche in folgenden digitalen Archiven beginnen:

Archiv der Gesellschaft Memorial

Feniks Datenbank des Archivs der FSO Bremen

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

What might be hidden in old pillow, how to read protocol writing, and why fillout out archive cards turns the history of the Soviet Union inside out.

Arseny Borisovich Roginsky, in addition to the fact that he instructed us to fill out these cards, once said (and I think he said it quite well) that we’re trying to turn our entire history of the Soviet Union upside down. Trying to turn the pyramid upside down. The fate of a person, one person, becomes the unit of measurement of history. Not the Party, the government, a congress, not anything else like that, but the fate of just one person. We add them all up: one person’s fate, another one, a tenth one, a twentieth, and that's what our country's history is. And wars, and victories, and a history of repression. It’s not possible for history to be only wonderful, only glorious, or only victorious. History is what it is.

And therefore, when the Memorial archive was being assembled, they thought for a long time about what focus to take, what the direction should be. We decided to collect not the FSB archives, but everything that’s been preserved in human memory. Everything from the families, everything in their homes. Sometimes it's a suitcase, and sometimes it's just a single item. And if we can add the records of a case to this one piece, then that’s just a bonus. After all, when we take an investigative file and read it... it's actually a lot of work to read an investigative file. It must always be remembered every minute that it was written by the investigator's hand. And the person, the subject of the file, is very dimly visible behind this record made by the investigator. It’s necessary to keep this in mind all the time, and it’s difficult, because almost every paragraph has a signature. He signed this and that and something else. He admitted it. Why did he admit it? Why did he admit it? We don't see anything of this.

Again, this is a topic of great, great research: this culture of protocol writing, the language of the protocol. But sometimes we can see that the interrogation began, let's say, at 19:15, and ended at 02:30. How long did it last? Seven hours. Three pages. What of those seven hours ended up on those three pages? Or maybe we read a paragraph, something like this: "On Fridays we held meetings and planned a terrorist attack against the leaders of the Party and the government." What does that mean? It means that on Fridays the men gathered after work and drank beer. Do you understand? But the investigator can’t write that. He needs to write something that you can be sentenced for. I'm just fabricating this [as an example]. But you really see the interrogation protocol, which is really written in such coded language, where there are no "get-togethers," but "gatherings," not "a group of friends," but a "group of conspirators" or a "gang." And sometimes this is the only source. The only one. There is nothing else. Therefore, if we can attach something to this document, something that is written in the subject’s own hand—a letter, an appeal, let's say, even to some higher-ups, a petition for review or an appeal for pardon, where he describes what happened to him—then that’s wonderful.

Any piece of paper is a huge treasure. Any piece of paper, not even a letter, but a fragment of a letter from a camp—that’s very rare and very valuable. Very few of them have been preserved. It's just these things. The fact that we have such a large collection is because we have been collecting these tiny things a bit at a time for 30 years.

Therefore, we have a completely different focus, a different attitude to documents. And, most likely, this is why I have regarded each such piece of paper as a personal treasure. And that's why there is such a reverent attitude towards the character, towards the hero. He becomes a hero, you know? They're really all my favorites. I know them all.

Once a man came in, about my age. That was about ten years ago. Or maybe he was a little younger than me. And he said that his mother had died. His mom had had a favorite pillow. She never parted with it. When his mom died, what did they do first? They ripped open the pillow. And inside, there were these scraps…not even scraps. He brought us this pile that included pillow feathers, pieces of paper, little bits of paper. But there are certain documents that…do you know how Sherlock Holmes was able to distinguish the Times editorial from all the others by one line? I could recognize the release certificate by one letter. It’s very distinctive. You can't confuse it with anything else. I told him, "This is a certificate of release."

And here’s an example that is absolutely brilliant. Once upon a time, a man came to us with a very literary surname, a common one. And I started looking for his grandfather. Well, it's not difficult to find his grandfather. His grandfather was shot, so we found him just in the blink of an eye. But the fact is that there are some such grandfathers, and when you look at them, you realize that the grandmother should be there, too. And we asked him, "What about grandma?" He says, "I don’t know. I don’t even know her name." "You don't know her name, but we do. Let us tell you what grandma's name was, and tell you what happened to her."

That guy left the meeting, as they say, on wobbly legs. But some time has passed. And on New Year's Eve, he appeared at our office with this great gift basket! A New Year's basket with everything you need for the New Year. Well, that was great. A year passed, and he came to us again and brought a basket again. Another year passed. He came to us again and brought a basket again. The first time was in 2017. Then imagine, he came again on December 29, 2023. And he brought us a basket and told us that it would always be like this.

Начать ваш собственный архивный поиск можно с электронных версий архивов:

Архив Научно-информационного центра «Мемориал»

Архив Исследовательского центра Восточной Европы при Бременском университете

You can start your own archival research with the digital archives:

Memorial Society archive

Feniks Database of the Archive of the FSO Bremen

_______

Sie können Ihre eigene Archivrecherche in folgenden digitalen Archiven beginnen:

Archiv der Gesellschaft Memorial

Feniks Datenbank des Archivs der FSO Bremen

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

A unique collection of children’s correspondence with their fathers in prison. Almost none of them ever saw each other again.

At some point, my colleague and I assembled several such collections. From our point of view, they’re completely unique: these are letters from fathers, written from prison camps.

While dad is at home... he comes in late and sees his child either already asleep or still asleep. Of course, he undoubtedly loves him. And undoubtedly, he thinks that Sunday will come, and he’ll go somewhere with his child, or maybe take him to the zoo. Or read him a book. And then dad gets arrested.

Of these sixteen people, very few were ever released. I think only three got out. All the others either died in the camp, or they were shot after being convicted a second time. But this powerful paternal instinct erupted in the camp conditions. They don't just write letters to their children that say “okay, obey your mother, study well, and get some fresh air.” They really give them something in those letters. It turns into a remote education, like the online education we had during COVID. They convey to them what’s important to them, what’s valuable to them.

These are very different people, and therefore they give very different parting words and instructions. One of our protagonists was a passionate philatelist. And even when he wrote letters to his son from the camp, he drew stamps by hand on these letters. Moreover, these stamps had a very immediate meaning: he painted on the stamps what was around him. Here he was sitting in Mountain Shoria, in a Siberian camp, and he painted a picture of the camp on a stamp. It's absolutely amazing. The most interesting thing is that his son had no way out, and he also became a philatelist. Well, what else could he do?

Or there was another case: an absolutely amazing, brilliant man. They are, of course, all quite brilliant. But some are really exceptional. Like Alexey Wangenheim, who founded the meteorological service in the Soviet Union. And he wrote these absolutely brilliant letters to his daughter, enlightening and educating her. The child was growing up while he was imprisoned in 1934, when she was four years old. He wrote letters to her until 1937. At first it was children's riddles, then all sorts of natural phenomena: a solar eclipse, spirals, and perspectives. All that, plus drawings.

Then he came up with a science. I don’t even know what it’s called: botanical arithmetic or arithmetic botany. He assembled herbariums. All this happened at Solovki. It must be understood that that’s what summers are like on Solovki — for about a month and a half, probably. He collected herbariums so that he could educate his daughter, letter by letter. He would number [the diagrams]: number one is one leaf and everything that can be found around it, number two is these two pine needles, and whatever else can be found around them. It's all just wonderful. This herbarium has been preserved and has been transferred to our archive.

And so each of them sends his children letters like these and tells them, from a distance, what he thinks is important. And we decided that we should collect these stories and share them, communicate how the lives of the children then turned out. Because if the son of a philatelist became a philatelist, then who was the daughter of a hydrometeorologist supposed to become? She became a paleontologist, the chief mammothologist of the Soviet Union. At her house, there were mammoth tusks just lying on the floor.

And I’ve been to their homes. I know these people. They’ve entered my life and become a part of it. I don’t know…maybe this is a slightly unnatural state for any other person. But, on the other hand, characters from literature also enter our lives. They also become our friends, and our characters, and our subjects. People whom we consult when necessary. Or we look up to them, or we orient ourselves to them. That happens, too.

Начать ваш собственный архивный поиск можно с электронных версий архивов:

Архив Научно-информационного центра «Мемориал»

Архив Исследовательского центра Восточной Европы при Бременском университете

You can start your own archival research with the digital archives:

Memorial Society archive

Feniks Database of the Archive of the FSO Bremen

_______

Sie können Ihre eigene Archivrecherche in folgenden digitalen Archiven beginnen:

Archiv der Gesellschaft Memorial

Feniks Datenbank des Archivs der FSO Bremen

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

An archive can do more than tell you about yourself. It can change your life.

What do you think: If we go outside and consider a hundred people, how many of them will ever have been in an archive? Or will have ever even consulted an archive? I think not one out of that hundred.

Because what is an archive in the view of a regular person? It’s some kind of incomprehensible thing. Probably some piles of old papers. And what could be in those piles? What would we look for there, why would we go there, and how would we go there? Can we go there?

If we’re talking about our topic, about the topic of repressions…what does that mean? Does it mean we have to go to the offices of the KGB? “Just walk right in there with your feet? Really? Why would I go there? I'm afraid. And then they’ll have something on me, some kind of records, and they’ll make me work with them. I don't want to, I'm afraid, I won't go there.”

Many such emotions come up immediately

I'll tell you honestly that I've been to the FSB archive many times, and every time I have to make an effort. I have to overcome myself. So it feels like: should I go to the archive and ask them something, or tell them anything? "No, I don't want to. Let someone else do it." And when people come to us now, I have to explain to them that I would go and submit [a request] in their stead, but I’m not allowed to do that. Because, according to the present rules, only a relative has the right to ask a question. And that person has to bring documents that show the relationship.

And this is a special matter. Although you may still find your birth certificate, how can you prove, for example, that a certain person was your grandmother's brother? In order to prove that they were brother and sister, we need to find their birth certificates. It's not practical. This is completely unrealistic. Let’s not deceive ourselves. And if we cannot prove the existence of the relationship, then the departmental archives, and let’s say this in a politically correct manner, consider that they have the right to refuse your request: "You do not have the right to see these documents."

But, in fact, not everything is so strict, because there is such a thing as the "termination of secrecy." The deadline for storing the document without access rights has passed. In common practice, it is considered that once 75 years have passed, everything should be transferred to the usual government storage. It's not like that here. Everything is much more complicated, trickier, and more confusing here. In one city things may be done one way, but in another city, it’s different. Or, if we are talking about the case files of people who were repressed, it may be that part remained in the FSB archive, and part was transferred to state custody. If such a case file is in the custody of the state, then things are easier. But if it’s in the FSB archive, that’s different. And if it’s in the archive of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, then it’s completely impossible.

And this search always turns out to be very multi-layered. Relatively recently, this one girl and I—she’s become a good friend—I think we searched for four years. We submitted so many requests…I don’t want to get the number wrong. Either 78 or 87. Because you have to feel your way through one of these searches.

There was an interesting story there. She knew that her great-grandfather had been arrested and something had happened to him. That's it. She didn't know anything else; she had an idea about which city it might have happened in. And then I started conducting the search with her. Well, what does that mean, that we worked together on it? She would ask me who to write to, and I would tell her whom to write to. I give her the address and the approximate text of the request. Then she somehow adjusts it in her own way and sends it off. She receives a negative answer that there is no information.

But, from my point of view, a negative answer is always an answer. It's always information. It’s clear that we’ve already poked into this corner, which means that we now have to expand our search.

And it went on like that for many years with no result. There is no information, nothing. No messages. The surnames in question aren’t in any of the records. And at some point, some information appears, and you immediately cling to this information and start thinking about what you can learn from it.

And as a result, we learned absolutely everything about this unfortunate great-grandfather of hers: when he was arrested, and the case against him, and what he was accused of, and what sentence he got, and where he was sent. We learned where he was sent. He was transferred from one place to another camp. And we found the other camp, too. And in that other camp—maybe even in the third, I can't say for sure now—he died. And we found his camp file and learned where he was buried. Not the grave itself, of course: that’s impossible. We found the location of the camp cemetery. She went there, and she was right to do it. And in the end, she wrote to me that she had changed her last name and now she lives under the last name of her great-grandfather.

She had never seen him. But there was such a degree, such a high level of involvement, such a need to touch his case and to follow up on it. Here’s how to look at it: he was trampled, he was killed, he was destroyed, his life was absolutely broken. So, do I just forget about him? Do I give up on him? Or do I do what I can to keep him from being forgotten?

Here again, it's still very different between one person and another . It seems to me that we can draw a line, analyze the situation, and say that a person wants to understand something not about another person, but about himself. "Who am I? This is my great-grandfather. One way or another, I’m a continuation of him." Sorry for saying something so terribly banal, but it’s something like this: "His blood flows in me; if I don’t know who he is, then how can I say something about myself?"

It sounds like a joke, but it really happened: a man from the tax inspectorate came to Memorial for an audit. As it turned out later, he was told, "Search until you find something." And he was sitting there with us in our room, because there was no other place for him to sit. We gave him a desk and a chair to sit on. Well, on the first day, everyone was kind of stiff around him, but then our work went on, we had lots to do, and no one was shy around him anymore, and everyone stopped paying attention to him. He was just someone sitting there looking through some kind of accounting stuff, so no one cared.

And after a while he came up and said, "Listen, what is all this? I’m sitting here, and all I can hear around me is ‘arrested,’ ‘arrested,’ ‘repressed,’ and ‘shot in a camp.’ It seems like everyone was arrested, repressed, and shot.’" We asked him, "Do you know anything about your grandfather or great-grandfather?" "Yes," he said, "I know he died during the war." I'm typing and I ask, "What's your last name?" Then I see that his grandfather was shot and is buried in Butovo. We say to him, "How do you know that he died during the war?" He says, "My mother told me." "Well, you see, he didn't die during the war." "This can't be real." But everything recorded in our database is supported. We still try to ensure that each bit of information is supported by documents, even by the scantest information, maybe even just one line. But this is a document that cannot be disbelieved. For example, a document ordering execution by firing squad. It’s impossible not to believe it.

And this young guy calls home in front of me and says, "Mom, I'm at Memorial right now. You told me that my grandfather died during the war, but he was executed by firing squad." Or maybe it was his great-grandfather. She says, "Yes, but you don't want to know that." How do you think it ended? The guy quit working for the tax office.

So many layers open up. I don’t know. Probably it’s not historians and archivists that should think and talk about this topic. It should be psychologists asking, “Why don't we tell anyone about this? Why don't we tell the later generations, the grandchildren of the repressed, our own children or even our grandchildren and great-grandchildren?” Everything is layers. It’s not so straightforward. Because, on the one hand, not asking questions is the beginning and the end of all this. Don't ask questions, don't say anything. "Why didn't you ask your mom?" "It was clear that you couldn't ask." I say, "Well, how was it made clear? Did she explain it to you?"—"Well, why explain it? It's just in the atmosphere." That’s number one.

Number two is this, and I’m guilty of this, too. We were all taught this. “Do not talk about everything that happens at home on the street. Look, the door is closed. This is our world, and that is someone else's. That world is the enemy. You can’t go talk to those people with an open heart.”

I even have to tell you that relatively recently I had my own trauma, because, as it turned out, I told my children the same thing. I may have done it unconsciously, but that's what I was taught. And some time ago, my youngest son came to me and said, "Listen, but you always told me that I shouldn’t tell anyone about what goes on here." And he says that he told his wife the same thing: You can't tell anyone what goes on at home. She asked him, "Why?" And he didn't know what to say. And he came to me, and I didn't know what to say, except that I was crying like crazy.

Начать ваш собственный архивный поиск можно с электронных версий архивов:

Архив Научно-информационного центра «Мемориал»

Архив Исследовательского центра Восточной Европы при Бременском университете

You can start your own archival research with the digital archives:

Memorial Society archive

Feniks Database of the Archive of the FSO Bremen

_______

Sie können Ihre eigene Archivrecherche in folgenden digitalen Archiven beginnen:

Archiv der Gesellschaft Memorial

Feniks Datenbank des Archivs der FSO Bremen

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

How archives change your outlook and idea of the past.

If truth be told, I'm not an archive guy. Moreover, I wasn't an archival historian—meaning that, while I have a degree in history, I never had that borderline religious or even academic notion of archives as the ultimate source of knowledge or the feeling that I am inadequate as a professional without them. But it so happened that while doing a project for Memorial, I found myself in Russia's State Archive, which holds the case files of all defendants in Soviet-era political cases—a collection spanning over 100,000 cases. It did more than leave a lasting impression; it completely overhauled my ideas of how I should approach my personal Soviet past, our collective Soviet past, and life in general. I have been thinking about it in various modes ever since.

The majority of such case files are kept in Federal Security Service archives in different regions of Russia, and access to them is limited. You have to either prove your relation to the person whose file you want to access, or submit a special request, but you cannot copy case materials unless you are a relative. Your time with the documents is also limited, so you may not be able to do everything you need.

Meanwhile, Russia's State Archive is a treasure trove. It is one of the very few Russian-language institutions that offer access to such cases in the first place. I should emphasize that I have seen tens of thousands of these cases. And here is what I think I could share...

As an aside, I feel it's important to make another general remark about the external framework. I believe the first thing that struck me was the very fact that these case files are still being stored—the files of people charged with political crimes, mostly under Article 58 of the Soviet penal code. Those materials were marked for “indefinite retention.” The defendants are ordinary, unremarkable individuals. The only knowledge we have of them is limited to a file that was put together to charge them with a crime.

Many do not even belong to the written culture. They would not have been able to write anything about themselves; they even signed their statements with a cross. My first human, literary, spontaneous response was to see a vast, sprawling Soviet conspiracy theory. The conspiracy was indeed immense: a giant number of supposed enemies that had spun their webs around every domain to do as much harm as they could. A cloakroom attendant from a village club was accused of putting her hair on the coats of Communist Party members in order to give them lice. Her file features an envelope with a lock of her hair and the lice test results. The cases range from hers to that of a guy who somehow managed to escape the interrogation chamber (an incredibly rare incident) and attempt suicide by jumping out of the window. He survived. And the investigation went on, with the photograph of the broken window added to the case file.

People's fates intertwine with one another because the general logic of an investigator is not to chase after individual wrongdoers but to “bust” an entire ring. This is how the trade works; it's more efficient and better for your career. As a result, one defendant should ideally bring three, five, a dozen more. And if you read the files in chronological order, you can see how these nets are cast and who is connected to whom. Thirdly, I couldn't shake off the feeling of going in circles, locked in an endless cycle of repetition of the topic of guilt: that we're all guilty of something, and that immense guilt is a heavy burden on our shoulders. We are all defendants in these cases. And we have to keep repenting or, on the contrary, defending ourselves from accusations of always falling short.

Put together, these three motifs can provide at least some insight into the kind of past we share and the elements of the past that made it into the present. This serves as the general framework for any story I could share with you today.

Начать ваш собственный архивный поиск можно с электронных версий архивов:

Архив Научно-информационного центра «Мемориал»

Архив Исследовательского центра Восточной Европы при Бременском университете

You can start your own archival research with the digital archives:

Memorial Society archive

Feniks Database of the Archive of the FSO Bremen

_______

Sie können Ihre eigene Archivrecherche in folgenden digitalen Archiven beginnen:

Archiv der Gesellschaft Memorial

Feniks Datenbank des Archivs der FSO Bremen

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

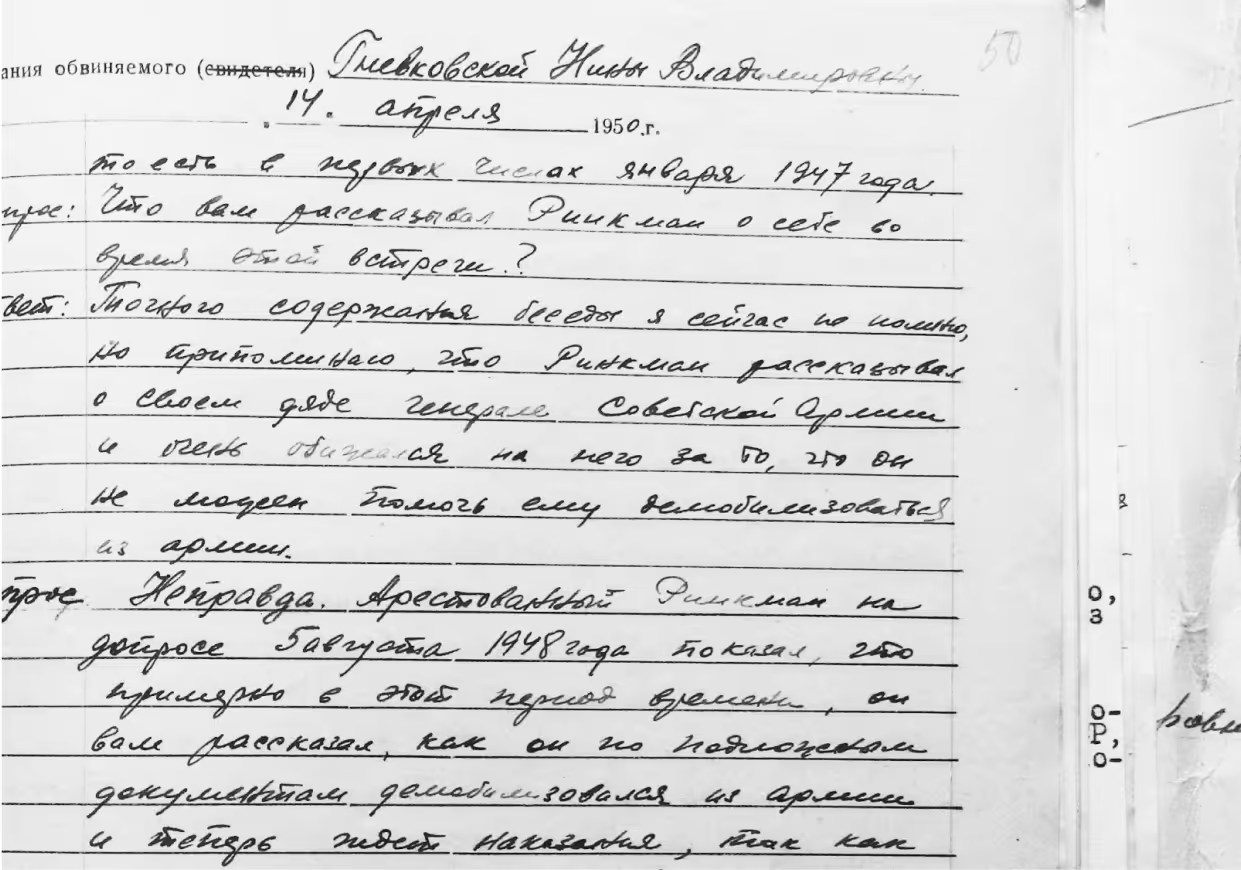

The story of Nina Gnevkovskaya, who was harassed by secret police chief Beria, was sent to a labor camp, then became an investigator and prosecuted dissidents, and finally demanded recognition as a political repression victim

This is the story of a woman called Nina Gnevkovskaya. A colleague from Memorial asked me to check in the Russian State Archive Catalog if her file was in the collection I was working on. Some dissidents mentioned her in their memoirs as an investigator who attended searches and behaved in a peculiar manner. As they wrote, she was not like the others. So I found her case file. Since the file was labeled with her name, it could only mean one thing: she was a defendant in this case, not an investigator. As it turned out, in the late 1940s, Gnevkovskaya, still a young girl, mingled with the Soviet “gilded youth.” They had either been born into privileged families or somehow made their way into circles that had access to trophy goods: early American jazz, fancy clothes, restaurants in hotels in downtown Moscow.

This was how it all began. At some point, Lavrentiy Beria, Stalin's secret police chief from 1938 to 1946, took an interest in her. His aide began stalking her, and eventually, she ended up in Beria's country house, where he raped her. The case has an unconventional way of describing it. There is no explicit mention of sexual violence, of course, but the complex structure of omissions speaks volumes. As we figured out, her relationship with Beria lasted for quite a while. Like all cases of this kind, her case ends with an indictment—an indictment against her for slandering certain members of the Soviet government, which is presumably a euphemism for Beria. What happened was that Beria raped her multiple times, and she told some of her friends about it. These conversations reached the wrong ears. Rumors began to spread. Gnevkovskaya ended up in a Gulag camp. It's not in the case file.

Overall, I had two reference points.

Both stories left a strong impression. I decided to try digging from both ends, and we managed to fill out the gaps, establishing what happened before and after. We found Nina Gnevkovskaya's Gulag memoirs, which suggest she was a model prisoner—not in the sense of trying to please the administration but in terms of doing the right thing from the dissident point of view. Reputable political prisoners later wrote about Gnevkovskaya that she was a decent girl and had never set anyone up. She worked in the kitchen—a privileged position in the camp—but never abused her privilege like many others did.

This already gives us a third angle. When we first meet her, she hangs out with the elite crowd; then we see her in a labor camp, and she seems like a decent person. Then we make another time jump: after Stalin's death and her exoneration, her testimony is even included in the extensive case against Beria. Some ten years later, Gnevkovskaya is already an investigator at the prosecutor's office. If you study her case file, it’s somewhat less of a surprise—after all, she had been a law student. Her career choice was not random, and neither was her social circle. She had the chance to mingle with affluent young people because her father worked for the state—not for the secret police but for the prosecutor's office. But the real twist comes later.

Even after all those years of working as an investigator, she still identified as a victim. And this got us thinking. We were wondering whether Nina Gnevkovskaya indeed underwent this kind of personal evolution or whether she emulated what appeared to be the most widely accepted societal norm of each given period.

Soon we learned there was even more to her story. We stumbled across her televised interview in an early 2000s political show dedicated to the events of 1968, when seven demonstrators gathered on Red Square to protest the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. At some point, Gnevskovskaya was in charge of the investigation into two of the protesters. She met with Larisa Bogoraz and oversaw an earlier case against Vadim Delaunay. But in her interview, she does not so much as mention her experience as a victim. What she says is, yes, I ran their case, and even though saying such things is frowned upon, all of these dissidents worked for America, of course, and they were self-interested and cynical, without any idealist views—no two ways about it.

This was another transformation she underwent, or at least the second time she showed that side of her personality, and it was fairly natural in the early 2000s, when the Putinist narrative was already taking hold.

Gnevkovskaya's case is one of a kind, of course, since we are rarely able to trace so many transformations. What kept drawing my attention was the degree to which our sources of information and the narrative itself allowed us to see so many classic Soviet tropes in a single person: “the cruel investigator,” “the miserable victim who must be exonerated and reinstated in her rights,” and so on. The complexity of such stories is that no one can be reduced to a single trope.

In this regard, a salient, very relevant presumption was aptly outlined by Israeli professor Igal Halfin. He drew the distinction between the real person behind the case and the defendant in the case, who has the same name but functions as a literary character inside the case file. Halfin inspired me to approach these cases as social realist novels.

Still, Gnevkovskaya's case stands out. It's not that she was charged with something particularly vile... But the allegations against her were meant to destroy her morally and emotionally. The file states many times that she is a woman of easy virtue, even though she was only 19 or 20 years old, and that she picks up guys at the Astoria or the Metropol... It is a very cliché Soviet intimidation technique: telling the defendants that they are not just politically but also morally corrupt. So her investigators drag her through all the variations of moral decay. Her relationship with Beria also highlights the moral aspect of her case, of course. As we can see from the multitude of stories about violence, any act of abuse leaves its survivor extremely humiliated. Interestingly, when she gets to sit at the other side of the interrogation table—I have only read a handful of her interrogations because getting access to dissident cases is generally more difficult—but in the first case against Vadim Delaunay, she speaks at length not about the transgressions he was being charged with but about some kind of inappropriate relationship he had with a young girl. I think she even mentions it to his parents. In her approach, I could see something very familiar—in fact, she was using a very similar tactic.

I had a feeling that her approach was not random at all. Different accounts of her behavior during searches mention that she always turned up well-dressed and wearing exquisite makeup. I believe it was Lyudmila Alexeeva who wrote that Gnevkovskaya would glance into the wardrobe and say, “How come you only have one coat? Where’s all that American money? What do you even spend it on?” This was her idea of presenting herself as a powerful, sexy woman.

If I am not mistaken, she never had children and never married. The consequences of her being wrecked morally at such a young age showed in various ways later in her life.

That said, I could be overreaching with psychological reasoning. We argued whether it was a good idea to think or say that what happened to her in the beginning—the account of her fall we read in her case file—explains, to some extent, her passion for breaking people and the very change of her role. This conclusion is probably too complicated and powerful for me to make. Whether we are allowed to make such statements is a big question.

What we can say based on the documents, I think, is that there exists a co-dependency between the investigator and the person they interrogate. They operate within a single language, a single value system in which moral decline can annihilate a person. Such an experience is utterly devastating.

And after surviving it, a couple of decades later, Gnevkovskaya uses the same arguments against young people arrested for protests in a completely different epoch.

Начать ваш собственный архивный поиск можно с электронных версий архивов:

Архив Научно-информационного центра «Мемориал»

Архив Исследовательского центра Восточной Европы при Бременском университете

You can start your own archival research with the digital archives:

Memorial Society archive

Feniks Database of the Archive of the FSO Bremen

_______

Sie können Ihre eigene Archivrecherche in folgenden digitalen Archiven beginnen:

Archiv der Gesellschaft Memorial

Feniks Datenbank des Archivs der FSO Bremen

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Why political prisoners' case files are a wealth of knowledge about the day-to-day life and spirit of the epoch.

Political prisoners' case files are a phenomenal source of information about the epoch, from mundane details to the fabric of life. A case file could contain something that was never supposed to be there in the first place—something that could not have been preserved by any other means. It's what they call a time capsule. Someone buries it, and you dig it out 50 years later and look inside.

From that moment on, all that matters is your perspective and your approach. Personally, I can say that I learned and understood a great deal about the daily lives of Soviet people from these files.

After all, they make for a very particular type of source as they document political—that is, nearly spiritual—crimes. Even the very description of a criminal act can suggest a great deal of tiny, quirky details.

As we analyze and narrate cases, we use a questionnaire for factual description, developed precisely because we quickly realized that charges brought against the defendant were only a starting point. Moreover, charges were often based on a template, and the investigation could also follow the same template. Meanwhile, the file could be telling a completely different story, and to hear it, you need to ask the right questions—or at least notice that something is off. As a result, you understand that the story you're looking at is not what it seems.

Say there is a tram conductor who comes to the cafeteria and doesn't like the soup there. He says,

This is a very rare case and a different criminal code article: number 154a. In the public domain, such cases are few and far between, especially if the convict was subsequently exonerated on these charges.

So we started from a completely unrelated plot and ended up with an entry about a cook who doesn't think much of Komsomol members, keeps flashing his partisan ID, engages in sodomy, and is very mediocre at his craft. End of story.

This case demonstrates the overlap between different realities and narratives, both political and unrelated to politics, in the same circumstances.

With very few exceptions, all of these people are completely unknown to the public. The main challenge, however, is that we initially see them exclusively as the perpetrators of a crime; they are defendants in a criminal case. From that point on, our job and our motivation is to pull at the thread and see the true story. On the one hand, we could simply approach them all as victims of Soviet terror. There is a common narrative, a general understanding that these victims matter, that they were not guilty of any crimes and that we must make their voices heard. But the next step is to try—since we have the chance to explore 100 pages of materials, sometimes rather “exquisite” in nature, about a completely unfamiliar individual—to try and see something the investigators did not mean for us to see. Something we can extract from the file by asking all sorts of questions.

And this is probably the part I enjoy the most. That is, my focus is not Soviet terror—it's the people. Their stories fascinate me a lot more than the repression apparatus. Its functioning has already been described reasonably well; Memorial has done an excellent job of it.

As for the ways it is applied to specific individuals, it's an immense problem because no two people are alike. While some cases are nearly identical, each person is unique.

Начать ваш собственный архивный поиск можно с электронных версий архивов:

Архив Научно-информационного центра «Мемориал»

Архив Исследовательского центра Восточной Европы при Бременском университете

You can start your own archival research with the digital archives:

Memorial Society archive

Feniks Database of the Archive of the FSO Bremen

_______

Sie können Ihre eigene Archivrecherche in folgenden digitalen Archiven beginnen:

Archiv der Gesellschaft Memorial

Feniks Datenbank des Archivs der FSO Bremen

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

A case file as a source of information about people who are “beyond the framework of any narrative”.

There are files on the kind of people who often end up beyond the framework of any narrative because they could not write and did not leave any memoirs or testimonies.

There is the case of a peasant, filed at the beginning of the second Five-Year Plan in a village near Moscow. The starting point of the case is a dog running around in the village carrying a sign: “At the end of the Five-Year Plan, you'll eat me as well, kids.” Evidently, it is a reference to famine. The village has been tasked with meeting targets but struggles with extreme poverty.

So a Communist Party commission from the nearby town arrives in the village to inspect the crops, and local peasants are to report on the targets they met—or, preferably, exceeded. The incident that follows is the substance of the case.

Afterward, when it becomes known (news travels fast), his escapade—the fact that he fed them with dog meat — is interpreted as an anti-Soviet act, a crime.

The most fascinating thing about his case is the political interpretation of the act. According to the reports, the delegation members were discredited, and village children followed them around and imitated barking. They were dubbed “dog eaters,” as though they were disgraced by being offered dog meat.

The peasant, in turn, most likely wanted to show them, “Look how poor we are; we cannot offer you anything other than this dog.”

What captivated me was the very nature of the act. There is a background to this story, of course. And there are plenty of details: at first, the party delegation did not understand what they were eating. They kept asking the peasant, “What kind of meat are we eating?” “I'll tell you later. Eat first, and then you'll find out.” The file also includes the conclusion of a veterinarian, who studied the bones left after the meal and established that they were dog bones.

At that point, we enter the space of interpretations: what the peasant saw or may have seen in his act, how the delegation members took it, and the village kids... The most relatable motive is probably the desire to mock and belittle the authorities. It is an act of bullying: feeding them with dog meat to humiliate them in the eyes of the villagers.

ТThe emerging meanings and the way they are described in the file, as well as the factual side of the case and the prosecution's theory, present us with a greatly generalized issue of understanding,

Of course, I immediately thought there had to be a cultural background. It was all the more fascinating that the act had been committed by someone completely ignorant. I do not want to overstate the degree of his illiteracy: He may have had a few years of school, but he was certainly not a reader of ancient literature who knows stories of someone being offered particular foods. He was not sophisticated enough to understand the semantics of his actions.

Since I often use Varlam Shalamov's works as reference points, I could not but recall his short story “A Day Off.” The protagonist, an imprisoned priest, attempts to say a prayer on a Sunday at the camp. Afterward, his fellow inmates, real criminals, invite him to eat with them. As they say, they came by a chunk of veal. Once he's eaten, they tell him that they killed the puppy this priest had fed to keep it alive. They killed a creature he treated as a friend. Learning that, he feels sick and vomits.

It's a brilliant short story, and Elena Mikhaylik offers a very profound semantic analysis of this work, focusing mostly on the interpretation of this scene as a Black Mass: You are being told you are eating lamb, but it was in fact substituted with dog meat. This case also includes an element of the Danse Macabre, so to speak.

I attempted to approach its manifestations from several perspectives. There are several possible explanations for why feeding dog meat to a delegation of party members is a political act.

At the end of the day, the peasant was sentenced to five years or so in a labor camp.

Начать ваш собственный архивный поиск можно с электронных версий архивов:

Архив Научно-информационного центра «Мемориал»

Архив Исследовательского центра Восточной Европы при Бременском университете

You can start your own archival research with the digital archives:

Memorial Society archive

Feniks Database of the Archive of the FSO Bremen

_______

Sie können Ihre eigene Archivrecherche in folgenden digitalen Archiven beginnen:

Archiv der Gesellschaft Memorial

Feniks Datenbank des Archivs der FSO Bremen

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

How the punitive system dehumanized people and what Varlam Shalamov has to do with it.

There was a case of a young woman, 19 or 20 years old, who was arrested for discrediting the Soviet Army—a “crime” that has gained popularity again in modern-day Russia. She was a nurse and served at a military unit in the summer of 1942 before being sent to the rear. In the company of her peers in Moscow or the Moscow Region, she started sharing what she'd seen: that everyone was retreating, that there were no weapons, and that entire villages surrendered. And that by and large, the Germans weren't that horrible. She even made her way across an occupied area without getting in trouble.

All of her stories were used as evidence against her. She denied everything, saying she was wrongfully accused by a soldier who was in the room and that she said nothing of the sort— that, on the contrary, she extolled the Soviet army for doing all it could to protect everyone.

The investigator tries to catch her in a lie. He says, look, here is what we have in your profile... As an aside, it is very important to first look at the defendant through their profile—a typical Soviet two-page question form: surname, name, patronymic, place of birth, family background, parents' occupation, Communist Party membership status. At that stage, one can already identify many of the constants. The nurse's profile states that she was an orphan and that she was raised in an orphanage.

So the investigator says, “You told us you're an orphan. But you are deceiving the investigation because we found your letters to your father and his replies. See, I caught you lying, so we cannot believe anything else you say.”

The next interrogation begins with the investigator returning to that story and insisting that she lied because they had found a photograph of the girl's father in her belongings. She says, “This isn't my father. I worked as a cleaner in an office and they had a filing cabinet with photographs. At some point, I needed to imagine the face of the man on whose behalf I was writing letters to myself. So I took this photograph and pretended he was my father.” The photograph in question is in the file; I even have it at home because I want to give it some thought.

She goes on to explain that she lived in a dorm and that, at some point, she developed a routine of sorts... Essentially, she was immersed in an imaginary world and even read letters from her fictitious father to her roommates.

Those were very nice letters. They are in her file, too, and they are not easy to read. They got me thinking about this lack of love. Interestingly, the letters mention her mother, but there is no correspondence with her. The “father” keeps writing that her mother is sick, and so on.