A search through the archives often turns into a detective story, an investigation that becomes more exciting the more it concerns you personally. We have put together a quest guide for searching through archives. Imagine you’re dismantling a mezzanine and find an old suitcase with all sorts of stuff in it. You don't know who these things belonged to, but the names and surnames on some of the documents and photographs seem vaguely familiar to you.

Of course, this instruction doesn’t apply to every situation. More specifically, we’re talking about the history of the USSR. The instructions show how much we can learn if we are not afraid to turn to the archives and how, with the help of archival research (and an old suitcase), you can suddenly find out amazing details about your family history.

NB. To illustrate the examples, we have used authentic documents, but all the stories of the characters are fictional and any coincidences are accidental.

Before moving on to the specific items and documents, here are some universal recommendations.

Take a closer look at the details

Inspect the found artefacts. At first glance, it may seem that they are not telling you anything. In fact, any detail can become a clue: a signature, date, stamp, background, or individual objects depicted in a photo.

Talk to your family

First of all, before visiting the archive, it makes sense to interview your relatives.

Their stories about the past may resemble a history textbook. In this way, memory unwittingly masks the events of private lives behind a widely accepted narrative.

It’s important to pay attention to the seemingly minor details: they can often become clues in your search. Of course, you’ll be very lucky if your relatives can tell you the names of the people who once owned the things in your suitcase: this is the most important information for processing any archival request.

What to look for

After examining the artefacts and interviewing relatives, you need to decide what type of information you’re looking for.

Was the person repressed? You’ll need to look for investigative documents.

Did they fight? You can try to find out about their military service.

Do you want to understand who the author or owner of the artefact you found was and what they were doing? Go ahead and search for personal documents.

Archives store many different materials that give us information about a person, their family, their places of residence and occupations, their studies and work, and their persecution or support from the Soviet government. Almost every document you receive will open up new ways for you to continue your search.

Where to look

This step may be the most difficult for those who have never dealt with archives, but our tips will definitely help you (see below).

Most of the documents of the Archival Fund of the Russian Federation are kept in state archives. They may be subordinate to certain departments, such as the FSB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Federal Penitentiary Service, or the Ministry of Defence (for more information about where documents may have been sent, see the tips below).

Each region and even every district has its own archive.

Finally, electronic databases will be an important aid in your search.

Prepare a request and go to the archive

You write a request to the archive in any format, specifying in detail what information you already know and what you want to find out. An important detail: you can get acquainted with investigative cases or any documents from regional and municipal archives without confirming kinship, which is only necessary to obtain copies of documents (regional archives can provide you with copies without proof of kinship on a paid basis). Unfortunately, this procedure does not apply in some departmental archives (for example, in Ministry of Internal Affairs or Registry Office archives).

Restore your family history

Step by step, you will learn something new about a given person, in turn discovering new ways of finding out about yourself. No one knows what path this will lead you down. It's both scary and interesting!

A few important clues about where things are stored:

Investigative files opened individually under Article 58 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR are usually stored at the regional offices of the FSB at the location where the case was established, but in some regions back in the 1990s they were transferred to regional archives. Here is a list of some regional archives:

Altai Territory — State Archive of Altai Territory

Altai Republic — Partially transferred to the State Archive of Socio-Political Documents of the Republic of Armenia (partially remained in the regional FSB)

Voronezh Region — State Archive of Socio-Political History of Voronezh Region

Republic of Dagestan — Central State Archive of Dagestan

Republic of Kabardino-Balkaria — partially transferred to the Central Archive of the Republic (partially remained in the regional FSB)

Kamchatka Territory — State Archive of Kamchatka Territory

Kirov Region — Central State Archive of Kirov Region

Kostroma Region — State Archive of Modern History of Kostroma Region

Krasnoyarsk Territory — A small portion of the cases was transferred to the State Archive of Krasnoyarsk Territory (most remained in storage at the FSB)

Republic of Crimea annexed by Russia — State Archive of the Republic of Crimea

Kurgan Region — State Archive of Socio-Political Documentation of Kurgan Region

Lipetsk Region — State Archive of Lipetsk Region

Moscow and Moscow Region — State Archive of the Russian Federation (files opened by the NKVD Directorate for Moscow and Moscow Region)

Nizhny Novgorod Region — Central Archive of Nizhny Novgorod Region

Perm Territory — Perm State Archive of Socio-Political History

Sakhalin Region — State Historical Archive of Sakhalin Region

Sverdlovsk Region — State Archive of the Administrative Bodies of Sverdlovsk Region

Tver Region — Tver Documentation Centre of Modern History (some of the files remained in the FSB)

Republic of Tuva — State Archive of the Republic of Tuva

Republic of Khakassia — National Archive of the Republic of Khakassia

Chelyabinsk Region — United State Archive of Chelyabinsk Region

Republic of Chuvashia — State Historical Archive of the Republic of Chuvashia

Yaroslavl Region — State Archive of Yaroslavl Region

The investigative files of convicts in Amur Region are currently stored in the Federal Security Service for Omsk Region.

The investigative files of the Red Army soldiers arrested at the front are kept at their place of birth.

Personal files on the administratively repressed—that is, exiles and deportees, as well as labour soldiers—are stored in the Department of Internal Affairs of the region where they served the sentence. Personal cards of ITL Bakalstroy and Tagillag labour soldiers are stored in the Municipal Archive of Social and Legal documents of Nizhny Tagil. Sometimes the documents of labour soldiers can be stored in the Federal Penitentiary Service where they served their sentence. For example, the camp cards of the Theological Camp are stored in the Federal Penitentiary Service in Sverdlovsk Region.

Prison files of former detainees can be found in prison archives.

Two more important types of documents are stored in certain regional archives: supervisory proceedings in court cases (about reviews of cases where a convict whose sentence had not yet entered into force filed a complaint against an unfair court decision) and filtration and verification cases of former Soviet prisoners of war (for more information about the storage locations of these cases, see here).

If you found out from military documents that your relative was missing at the front, try searching for them in the databases of the repressed: Often this status in documents sent to the family was attributed to those who were arrested and subsequently convicted. It is not often the case, but it happens that even those whom the family considered to have died in battle turned out to be repressed, and the relevant documents are available. The priority here is investigative proceedings, as they were subject to the strictest reporting. If you have a certificate of death at the front, but you see the date of execution in the database of the repressed, you can be sure that the second source is more reliable.

List of the most important electronic resources for searching by name:

Databases of prisoners of war:

Examples of databases on the websites of Russian archives:

The photo shows two men, along with the inscription: "Joseph, Vladimir." Their names don't tell us anything. On the back the following is written: "Party comrades I. M. Krenkel and V. L. Smirnov, Moscow, 1937."

First of all, we go to the relatives. Since they could not help us in this case, the year 1937, one of the most terrible in Russian history, suggests that the search can begin among the repressed. There is a high probability that the people in the photo will be on the lists of victims of terror.

First, you need to set the full names and dates of birth of the people depicted in the photo. Two databases of victims of political repression can help in this: the Database of Victims of Political Terror created by the Memorial society and the Open List.

If we are lucky, the names will be found: Now all we need to do is establish a storage location for the case, send a request, and prepare for a trip to the archive. If the mentioned people were not on the lists, do not despair: They may be mentioned in the party lists (more on this below).

We have found both people in the photo in the lists of those repressed in Moscow. Investigative cases were opened against all the repressed. They can be stored in one of the following archives:

The Central Archive of the FSB (this is generally the standard starting point when searching for cases of victims of political repression). It contains the files of those arrested by the Central Apparatus of the state security agencies (usually this institution dealt with the cases of prominent party, military and cultural figures, officials and business leaders). In addition, the Central Archive of the FSB stores information about subordinate archives.

The State Archive of the Russian Federation, in the collections of which are cases of those arrested by the relevant department of the NKVD in Moscow and Moscow Region.

From Smirnov's case, we learned that he lived on 1st Samotechny Lane at Apartment 15, No. 15. The next step is to go for an extract from the house records. Unfortunately, this luxury is available only in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Almost nowhere outside of these cities have the house records from the 1930s to the 1950s been preserved. The house record contains not only information already known from the investigative case—about the members of the family, nationality, or place of work—but also about when and where a person left their apartment, who stayed with them, and who their neighbours were. For an extract, we go to the regional archive: in our case, the Central State Archive (CGA) of Moscow.

There is usually a lot of useful information in investigative cases. For example, we find an extract from the minutes of a Special Meeting on the Smirnov case. The stamp on it says that the convict was sent to the Northeastern Camp. The name of the camp in his investigative documents allows you to access his camp file.

To obtain a camp file, you need to contact the Department of Internal Affairs of the region where the camp was located. We are writing a request to the Department of Internal Affairs of Magadan Region.

If the place where the sentence was served is unknown from the case, you need to contact the Main Information and Analytical Centre of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The centre stores the general file of prisoners and can redirect the request to where the camp documents are stored.

The second way to search is through Party documents. The Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI) keeps the card index of Party members and registration forms, and the protocols of admission and expulsion from the Party are in the regional archive of the region where the relevant decision was taken.

For a quick execution of requests to RGASPI (via the website), you need to know the number of the Party card, and if this is not available, the dates of entry and expulsion from the Party.

If you do not have this information either, you will have to personally go to the archive and ask for help from the staff.

RGASPI can tell you in which other collections you might try looking for the people in your photo. Smirnov is a common surname, but finding I. M. Krenkel, who was expelled in 1937, should be much easier.

We learned from the registration form of a Party member that Krenkel joined the Party in Moscow in 1928. Knowing this, we can continue the search in the CGA of Moscow. The protocols of joining and being expelled from the Party are kept there. Among other things, the reasons for the expulsion and the arguments of the members of the commission present for or against the decision to expel are given.

Here's what we managed to find out based on the results of an archive search. The people in the photo are Party comrades Joseph Krenkel and Vladimir Smirnov. The friends lived in the centre of Moscow and graduated from Moscow State University together. They joined the Party in 1928, and both were expelled shortly after this photo was taken. Krenkel was sentenced to death for "participating in a counterrevolutionary Trotskyist wrecking organisation" by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court. He is buried in Kommunarka, a settlement outside of Moscow. Smirnov was sentenced to eight years in camps on a similar charge at a Special Meeting. He was sent to one of the harshest Gulag camps—the Northeastern one in the Magadan Region (at that time in Khabarovsk Territory). He died in 1944, a year before he was due to be freed. According to camp documents, the history of Vladimir Smirnov's imprisonment is known: passing through one camp department after another, he eventually ended up in the hospital of the village of Stekolny, where he died of a "decline in cardiac activity" in January 1944. The camp file does not contain a burial site, but the website of the Necropolis of Terror and the Gulag project suggests that it could have been a cemetery in the village.

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

In front of us is an embroidered napkin with an inscription on it: "Larusya, love your mother. 18/10/1938.” On the back there is a tag with an inscription in chemical pencil: "Akmolinsk."

We do not know who Larusya is or how she or her mother are connected to Akmolinsk. It is only obvious that the napkin’s inscription was made by the mother of a certain Larusya. Also, the date of 1938 suggests a high probability that the mother made this napkin in custody.

As always, the surest and simplest thing is to ask our relatives. To start the search, find out at least the full name of the person and the year of birth (an approximate one will do). We learned that the author of the napkin was Anna Konstantinovna Bershinskaya and that she was born in the early 1910s.

If Larusya's mother was repressed, then an investigative case will have been opened against her. If we know the name and year of birth but not the specific region in which the person was tried, always contact the Central Archive of the FSB first. Investigative files are stored there, or there are indications about their storage location in a subordinate archive (for more information about finding an investigative file, see the story about photos of Party comrades).

In the investigative file, we found a personal statement from Anna, where she writes that her daughter (hopefully the same Larusya) was sent to the Verkhotursky orphanage (Sverdlovsk Region). Now we need to determine which regional archive to contact for information about orphanages.

We need an archive that stores documents from specific organisations, and most often this is not the main archive of the region. On the website of each archive there is general information about its collections and a guide: a list of all collections with an indication of the time of creation of the documents that are included in it and a brief description of each collection. In our case, after studying the certificates from various Sverdlovsk archives, we go to the Documentation Centre of Public Organisations of Sverdlovsk Region for information about orphanages.

An important clue is the city of Akmolinsk indicated on the back of the napkin. Most likely, it was there that Anna Bershinskaya served her sentence. Camp documents in Kazakhstan, as well as in Russia, are kept in the archives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. There we are looking for a camp card or a camp file (if the person died in custody).

So, what have we learned? Anna Bershinskaya embroidered this napkin while serving time in the Karaganda Camp. With the help of an investigative file, it turned out that she was arrested on 3 November 1937 as a "family member of a traitor to the fatherland" shortly after her husband's arrest and sentenced to eight years in the camps. She served most of her sentence in the seventeenth women's camp department of the Karaganda Camp (in Akmolinsk), where the wives of convicts were held by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court. All this time, she was trying to look for her daughter Larusya (the diminutive form of the name Larisa), who was sent to an orphanage after her mother's arrest. Anna sent homemade things to her relatives who remained free in the hope that someday her daughter would receive them and remember her mother. Larusya's last name was changed in the orphanage, but after her release in 1946, her mother managed to find her and bring her home.

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

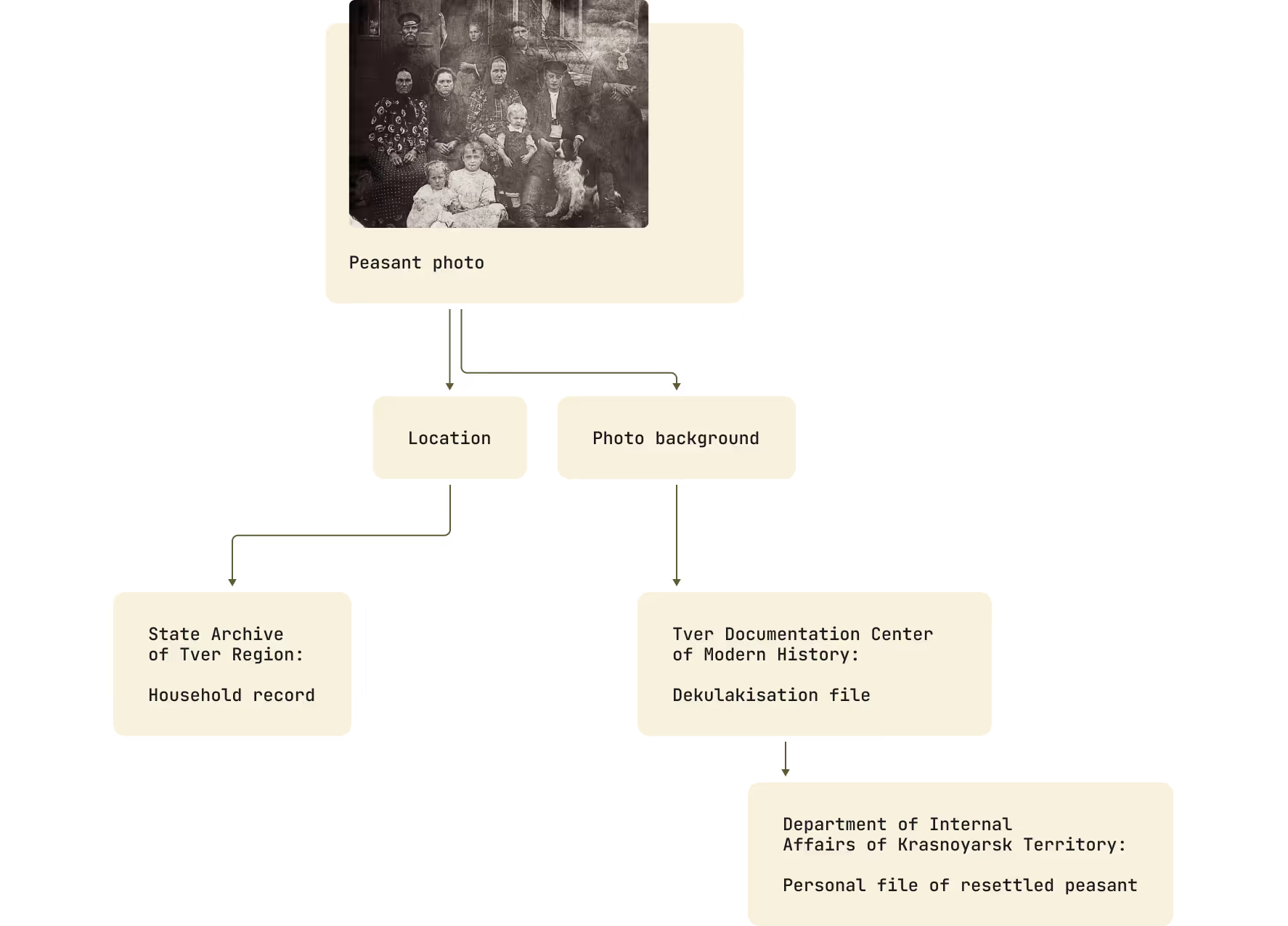

In the suitcase we found a group photo against the background of a log house, with an inscription on the back: “Our Bernovo.”

We don't know anything about the people in the photo. If the relatives can't remember anything either, then the photo itself gives us a couple of clues.

Location: The village of Bernovo is located in the Staritsky District of the Tver Region. Knowing the name of the village, we can go in search of a household record. These records contained the following information: the members of the family, the working activities of its members, levels of literacy, and economic data. Two kinds of archives can help us find such records: archives at the municipal (that is, the district) level and the regional level.

In our case, the district level is the archival department of the administration of the Staritsky District of the Tver Region, and the regional one is the State Archive of the Tver Region.

The background against which the photo was taken: In this case, it is a peasant hut. A family living in such a house could have been dispossessed in the early 1930s. To find the case of dekulakisation, we go to the archive that stores documents of state authorities that existed during the Soviet period. This is usually a state regional archive or an archive prefaced by the words "socio-political," "administrative," "legal," or "updated." In Tver, the archive we need is called the Tver Documentation Centre of Modern History. There we find the case of dekulakisation. It states that the family was exiled to the Krasnoyarsk Territory.

We are now going to search for the personal files of the exiles. They are usually kept in the local archives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. In our case, the information is in the Department of Internal Affairs of the Krasnoyarsk Territory.

As a result of our search, we found out that the photo shows the family of Yegor Artemyev, who was dispossessed in 1931. We learned from the household record that the farm had four horses and six cows, as well as 12 sheep and goats. In addition to the house, Artemyev had an outbuilding and employed one farmhand to work on his site.

It became clear from the personal file of the resettled peasant that not everyone reached the place of exile. The youngest son, Misha, who was three years old at the time of dispossession, did not survive the arduous journey. There was an addition to the family at the special settlement: in 1939, a daughter, Olga, was born. In 1944, the family was removed from the special settlement register.

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

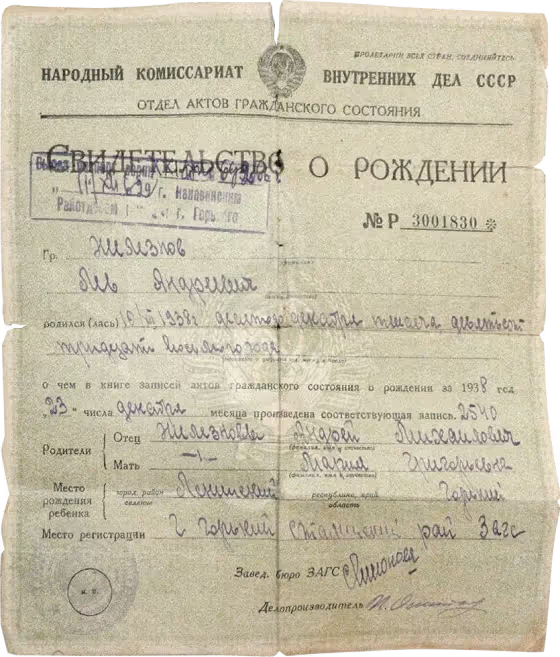

We found the birth certificate of Lev Andreevich Zheleznov, dated 23 December 1938 and issued in Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod).

If the survey of relatives did not yield anything, we put on our archivist–detective cap again and turn to the found artefact.

A cursory search of the names of the parents (Andrey Mikhailovich Zheleznov and Maria Grigoryevna) did not yield anything. This may mean that the child was raised in an orphanage. It is known that the names of both children and parents in orphanages were often changed. Thus, in the birth certificate issued to the pupil upon leaving the orphanage, the name indicated often differs from the real one. Sometimes there was a dash in the columns with the names of the parents.

At the same time, information about the real name of the child and their parents can sometimes be found in the documents of orphanages. This is where the year and especially the place of birth indicated in the certificate will help us.

The documents of orphanages are usually stored in regional archives (we talked about this in more detail in the story about the napkin from the camp). The exception is the orphanages that still exist, in which case the archive at the institution itself should be investigated.

Following the data from the birth certificate, we contact the Central Archive of the Nizhny Novgorod Region. There, in the documents of the orphanage, we find the real names of the parents: Andrey and Evgenia Zhelezov. Now we can try to find out something about them. Since the parents were apparently repressed, we look at the electronic databases of victims of political repression.

The father's card was found in the Memorial database. The source of the entry—the Memory Book of the Penza Region—indicates the location of the search for the investigative case. Most of the investigative cases are in departmental custody in the archives of the regional FSB, and only in some regions have the cases been transferred to regional archives. No cases have been transferred to the Penza Region, so we are writing a request to the FSB for the Penza Region.

From the interrogation protocol in the investigative case, we learn that the parents married in 1930 in Saratov. Now we can find their marriage certificate. All records of civil status acts registered after 1918 are kept in the archives of the registry offices.

So, we managed to find out that Lev Zheleznov's real surname is Zhelezov. Obviously, the letter was added to hide the connection with the repressed parents: Andrey Zhelezov was arrested in Penza in 1939 and soon shot as a "spy." Before his arrest, he raised his son alone: the protocol of his interrogation in the investigative case revealed a tragic family story about the death of his wife Evgenia during childbirth.

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

We have in our hands a letter sent from the front, near Bryansk, in 1941. It is addressed to a family; the author begins it with the words, "Good afternoon! Hello, Dad and mom, brother Borya and sisters Lena and Galya." Saying goodbye, he writes, "I am looking forward to your reply. Kissing you hard. Yours, Leva."

Once upon a time, in family stories, we heard about a certain grandfather named Leo, all trace of whom was lost in the war.

First of all, let's try to clarify his full name with relatives. The name gives us the opportunity to find information about dates of conscription and retirement from the army and about his military history, awards, and injuries. The search can begin with sites created under the auspices of the Ministry of Defence, which collects all available data about Red Army soldiers:

Electronic resources: The general Memorial data bank and the Memory of the People and Feat of the People databases. In the card on the website of the Memorial data bank, we found the place of conscription. Military registration documents are kept at military enlistment offices in the region where the person was called up for service. Leo's military journey began in Vladimir, so we appeal to the department of the military commissariat of the Vladimir Region for the Frunzensky District (where he was assigned).

From the card on the Memory of the People website, we learned that the Red Army soldier had an officer's rank. This means we can find his personal file. It could be stored in one of two places depending on the date of death of the serviceman. If he died before 1991, you need to contact the Central Archive of the Ministry of Defence or, if later, the Military enlistment office at the place of residence before death.

The originals of the documents published on the electronic resources of the Ministry of Defence are stored in its Central Archive. The archive's collections are much more extensive than those that have already been digitised and published, so a request can help us get more extensive information about a person. Without a confirmed relationship, we only have the right to request an information certificate from the archive. This will allow you to understand exactly what documents about a person are stored in the archive collections.

If we add the location to the name (where the email was sent from), we can try another search path. During the German offensive in the Moscow direction, hundreds of thousands of Red Army soldiers were captured. The names known to date are collected on special electronic resources:

Many Red Army soldiers who were captured were classified as "traitors to the fatherland" upon their return. Criminal cases were opened against them under Article 58 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR. To find out if this has affected your relative, you can access the databases of victims of political repression or make requests to the Central Archive of the FSB and the Main Information and Analytical Centre of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (for more information about the search procedure for investigative documents, see the description of the search for photos of party comrades).

So, this is what was discovered. The author of the letter is Lev Ivanovich Karpushkin, our great uncle. Judging by the documents on the website of the Memorial data bank, he was born on 27 July 1916 in Vladimir. He was drafted into the army in 1934 and entered the war with the rank of senior lieutenant. In 1942, he was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. Lev served as navigator in the 455th Aviation Regiment of the 36th Long-Range Aviation Division. After studying the documents of the Memory of the People website, we learned that, in 1943, Lev was declared missing, and later it turned out that he was captured near Bryansk. From 1943, he was in the Stalag Luft 2 POW camp for pilots. On 29 April 1945, he was repatriated to the USSR. Following his repatriation, all trace of him was lost: after checking the databases of victims of repression, we did not find his name in the lists.

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

In front of us is a personal certificate from the Vorkutaugol plant, issued to Praskovya Semenovna Bogomolova to commemorate Railway Workers' Day in 1962.

The most important clue contained in the letter itself is, of course, the name of the enterprise—Vorkutaugol.

We were lucky: Relatives not only told us that Praskovya was our grandmother's cousin, but also remembered the year when she retired from the plant, 1963. This is very important information, since archival inventories related to employees of enterprises are organised by year.

So, since the Vorkutaugol plant still exists, we just need to make a request to the archive of the enterprise. Some of the documents of the enterprise, especially ones relating to the early Soviet period, could have been transferred to state storage in the regional archive (collections of liquidated enterprises are also stored there). In our case, this is the National Archive of the Komi Republic.

The location of the enterprise indicates a possible repression. In Vorkuta, which was surrounded by a Gulag in Soviet times, freed prisoners from the surrounding camps often stayed on to work. Therefore, other possible sources of information about Praskovya Bogomolova are the databases the Victims of Political Terror and Open List, as well as the general file of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Department of Internal Affairs of the specific region where the camp was located. In our case, this is the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Komi Republic and the Federal Penitentiary Service of the Komi Republic.

As a result, we found out that Praskovya Bogomolova, who was awarded a diploma in 1962, worked at the Vorkutaugol plant while still a prisoner. She was sent to the camp in 1947 after being convicted on charges of "anti-Soviet agitation." In 1954, she was released and stayed in Vorkuta, continuing to work at the plant until her retirement in 1963.

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

In front of us is the student ID of Dmitry Nikolaevich Garkunov, a student at Tomsk University, from 1939.

Uncle Dima, our grandmother's brother, is remembered in the family only from his younger years. After graduating from the institute, he left his hometown, and during the war all trace of him was lost. The student ID is all that remains of his memory.

The ID indicates the university and the year of admission—these are the keys to finding out about a student's personal file. From a personal file, you can learn not only about someone’s studies but also some details about Dmitry's life before entering the university. Usually, personal files are kept in the archive of the university, but the files of students from the early Soviet period (until the 1950s) could be deposited in the regional archive. In our case, we contact either the archive of Tomsk State University or the State Archive of the Tomsk Region.

Thus, from the personal file of student Dmitry Garkunov, we managed to find out that he came from a large family with four brothers and sisters. Before entering the university, he lived in the Tomsk village of Palochka. Dmitry graduated from high school in 1935. He was "excellent" in all subjects, receiving top grades in everything except Russian, for which he received a grade 4 (B). He entered the Faculty of Physics, where he also had significant academic success as evidenced by an attachment to his personal file. Before entering university, he worked at a vegetable supplier. His personal file contained an appraisal from his workplace, in which the director of the enterprise noted his responsible attitude to his duties and commitment to a Stakhanovite work ethic.

Изображения: Научно-информационный и просветительский центр «Мемориал», Исследовательский центр Восточной Европы, Государственный архив Российской Федерации (Ф. 10035; Ф. 10035. Д. П-1889; Ф. 10035. Д. П-27759; Ф. 10035. Д. П-10874; Ф. 10035. Д. П-12311; Ф. 10035, Д. П-26286; Ф. 10035. Д. П-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (Ф. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), База данных жертв политических репрессий в СССР «Открытый список», Музей «Мемориала», Наталья Барышникова / «Мемориал», sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Музей Преображенской психиатрической больницы им. В.А. Гиляровского, Российская государственная библиотека, Государственный архив Вологодской области, Воркутинский музейно-выставочный центр, Электронная энциклопедия Томского государственного университета, Интернет-аукцион «Мешок», HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Images: SIEC Memorial, Research Centre for East European Studies, State Archive of the Russian Federation (F. 10035; F. 10035. F. P-1889; F. 10035. F. P-27759; F. 10035. F. P-10874; F. 10035. F. P-12311; F. 10035, F. P-26286; F. 10035. F. P-745), Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (F. 589. S. 3. F. 6917), Open List database of victims of political repression in USSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum of the Preobrazhenskaya Psychiatric Hospital named after V.A. Gilyarovsky, Russian State Library, State Archives of the Vologda Region, Vorkuta Museum and Exhibition Center, Electronic Encyclopedia of Tomsk State University, Meshok Online Auction, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department

Bilder: WIAZ Memorial, Forschungsstelle Osteuropa, Staatsarchiv der Russischen Föderation (F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035; F. 10035), Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (F. 589), Russisches Staatsarchiv für sozio-politische Geschichte (F. 589. Оп. 3. Д. 6917), Open List Datenbank der Opfer politischer Repression in der UdSSR, Memorial Museum, Natalia Baryshnikova / Memorial, sokirko.info / CC BY 4.0, Museum des nach V.A. Gilyarovsky benannten psychiatrischen Krankenhauses Preobrazhenskaya, Russische Staatsbibliothek, Staatsarchiv der Region Wologda, Museums- und Ausstellungszentrum Workuta, Elektronische Enzyklopädie der Staatlichen Universität Tomsk, Meshok-Online-Auktion, HarperCollins Publishers, Wikimedia Commons, Sam Hughes / CC BY 2.0, Rijksmuseum, National Archives and Records Administration, Cumberland Police Department